London had a socialist government in the '80s

I saw amazing archival documents showing the GLC's activities and how they were run

Back when Ken Livingston was mayor of London the first time around the Greater London Council (GLC) was the municipal government and they did a fair bit to try to decentralise politics and get communities to control things for themselves.

I first heard about this as a result of Mumbi Nkonde and Debs Grayson who showed me their project GLC Story at a teach-in event called World Without Borders around 2018, held in solidarity with the Stansted 15 defendants. Mumbi provided insights from the archives on the history of local deportations resistance, which they had gathered from their project documenting the GLC.

Through a lot of research and interviews the project shared stories from elder community organisers in areas like community arts, Black arts, LGBT services, policing, deportations, and resistance to gentrification, all of whom were people involved with London government.

I thought it was surprising that a British governmental body could be so outright socialist because I have never had this in any of the years I've been alive.

When I was doing my Masters I had a module where I could pick a museum or archive to do a placement in — I picked the LMA and researched this story, finding interesting material there, getting the material scanned. Then I wrote this article that I sent to Museums Journal.

It was originally published here and in their March/April 2023 issue.

Is London a place of resistance where people are empowered to improve how they live? Is it the impersonal and unfriendly city of popular imagination? If so, how can it become a more caring place?

Questions like these come up for those exploring the London Metropolitan Archives, where material traces of the city’s recent past provide an enticing way to connect with the politics of our lives today.

From 1965 to 1986 the Greater London Council (GLC), based at County Hall on the River Thames, existed as a layer of government between local councils and central government.

Ken Livingstone, who was dubbed “Red Ken” in the press for his left-wing policies, was the leader of the GLC from 1981 until it was abolished by the Conservative government in 1986. Municipal government did not appear again in the city until the founding of Greater London Authority (GLA) in 2000.

Ambitious aims

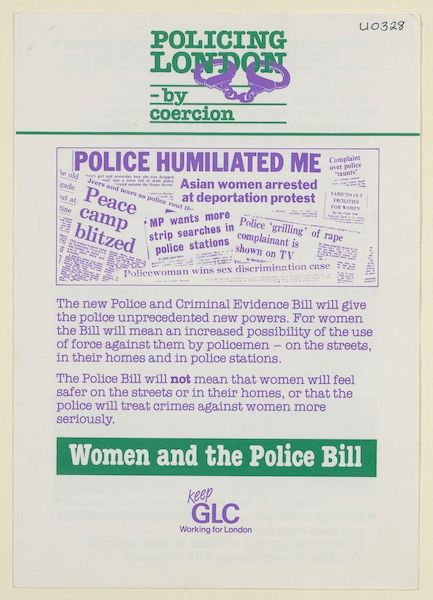

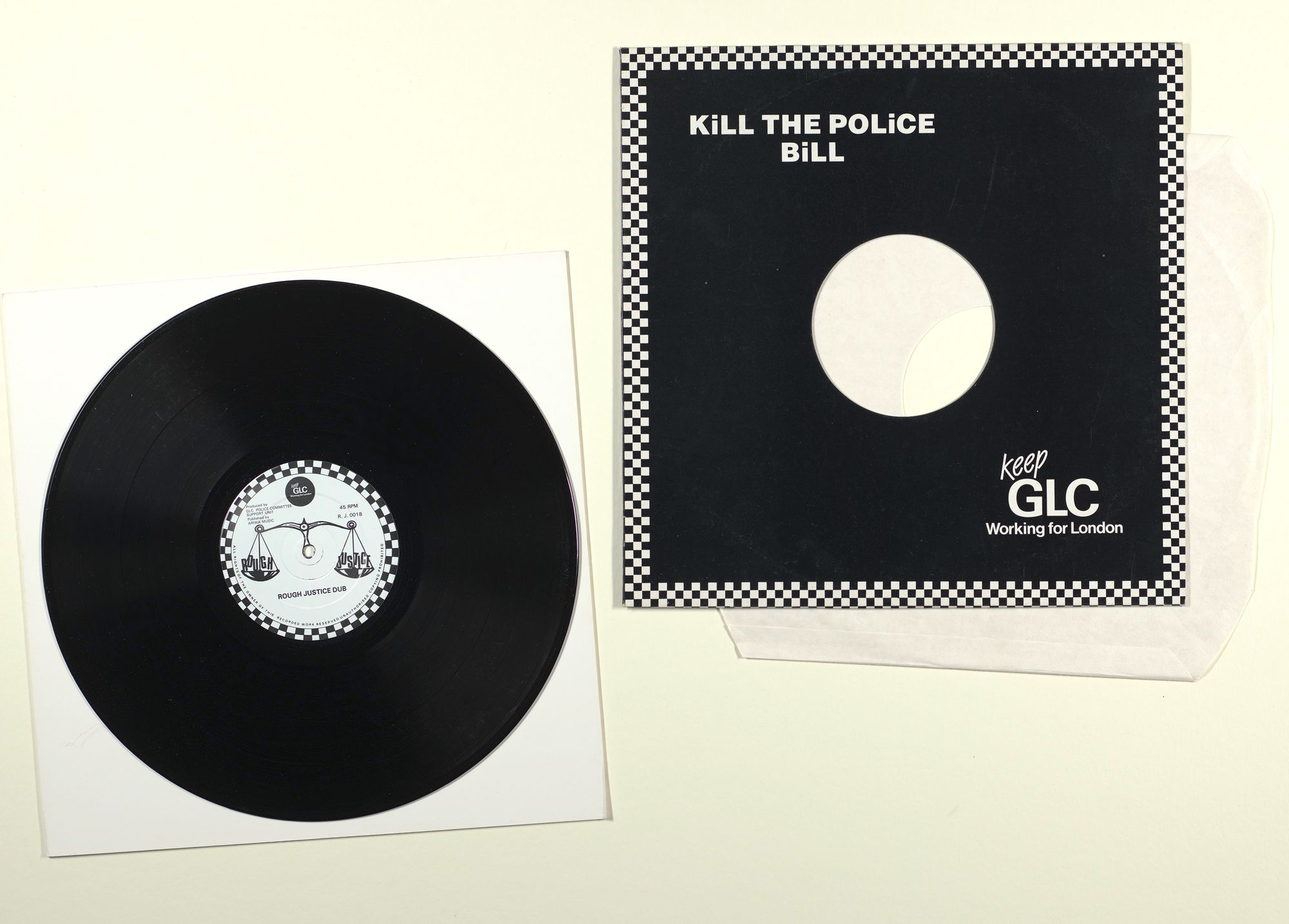

The London Metropolitan Archives holds GLC records from 1810-1988. This includes material related to the radical work that took place during the years when the Labour party came to power in 1981 on a manifesto that championed anti-sexism, anti-racism, LGBT rights, workplace democracy and community-controlled development.

Meeting minutes, reports and publications detail public education campaigns on racism, the creation of police monitoring groups, support for co-operatives, the funding of Black art forms, and more.

Despite the political significance of this period, many people are unaware of this radical experiment in local government. What are the reasons for the GLC’s absence from collective memory?

“I think local government doesn’t grab people – it’s not in the least bit sexy,” says Di Parkin, who worked on the Women’s Committee Support Unit at the GLC. She is one of the people interviewed for the GLC Story, an initiative to gather the memories of the policymakers within the GLC and community organisers they were consulting with.

Through the oral histories, archives and collections held independently and by public institutions, a picture emerges of the successes and failures of a radical movement, giving today’s community organisers a blueprint for social transformation.

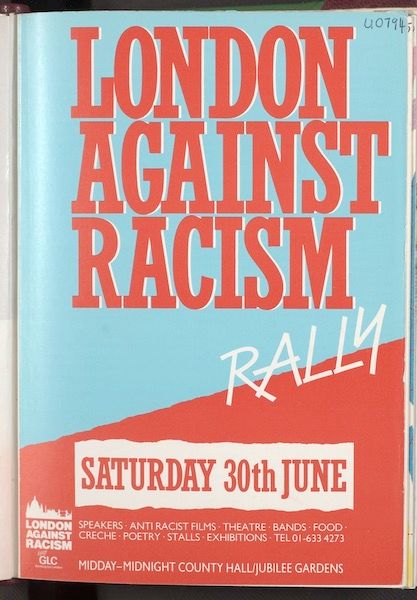

Take, for example, the GLC’s 1984 Anti-Racist Year, a project Livingstone came up with to try to get local councils and central government more in alignment with the GLC.

This project tried to popularise its work by uniting people around the issue of racism as it affected various areas of life, from employment to housing. The GLC raised awareness through publications, education, cultural events, and liaising with organisations such as religious groups.

Emotive words

Various media campaigns supported this mission. One poster, with an illustration of a Black mother and child, bore the slogan: “When was the last time you saw a Black Madonna? There is racism in the church too.”

Other posters ask: “Where would Margaret Thatcher have got to if she’d been Black?” and “Nearly a million Londoners are getting a raw deal because the other six million let it happen.”

The campaigns had varied success. In his 1987 book There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack, Paul Gilroy, the founding director of UCL’s Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the Study of Racism and Racialisation, recalls racist graffiti responses to the slogans on billboards.

In answer to the question about Mrs Thatcher, one vandal wrote “to the front of the housing queue”. In response to a statement about kicking out racism, the word racism was crossed out and replaced by “blacks”. Gilroy felt that anti-racist policies were hindered by impact-driven media campaigns that were simplistic due to their reliance on ideas of Black victimhood.

Tabloid media campaigns deriding the GLC often focused more on its cultural policies than its economic ones yet economic support represented a significant portion of its work. Examples of the ethnic minority businesses and workers the GLC supported include a music co-operative in Brent, a toy company making Black dolls and the expansion of an Asian snack factory in Woolwich.

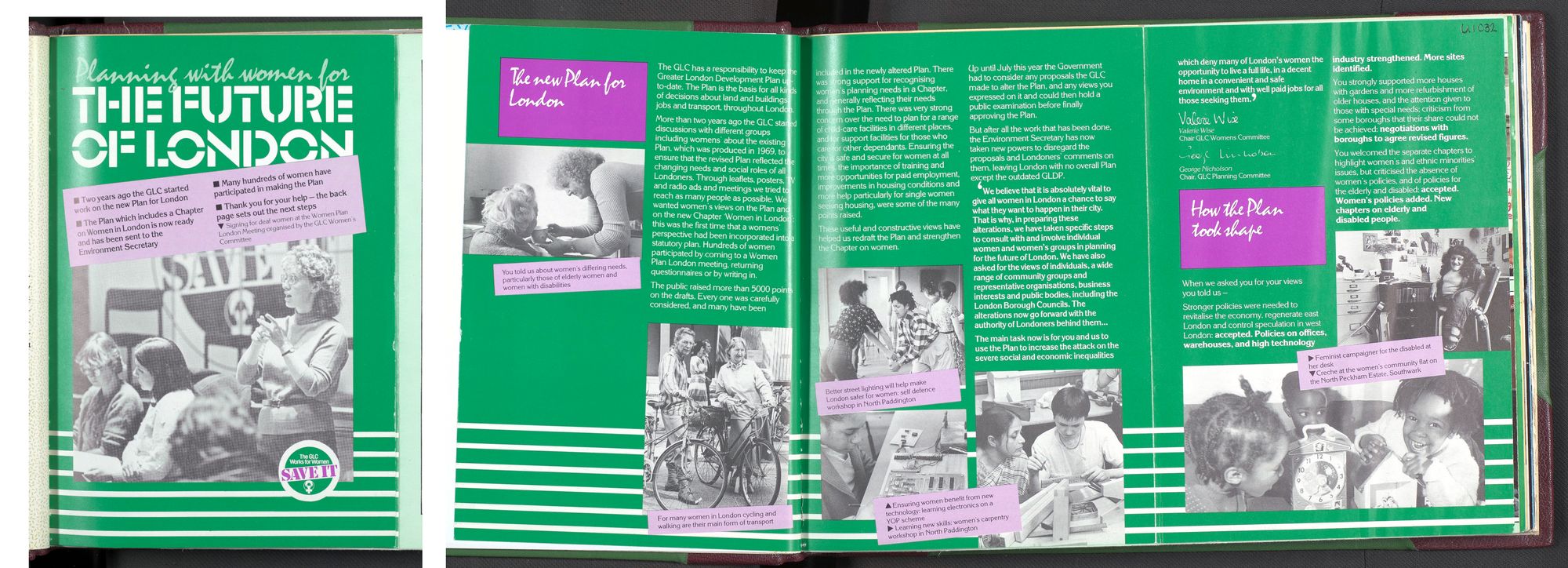

There were also groups supported by the GLC that encouraged political activity around development proposals. This included facilitating a People’s Plan for Newham in opposition to the City Airport plans, as well as gathering public contributions on making the city more accessible from a feminist standpoint.

People power

Hilary Wainwright worked on the GLC’s Industry and Employment committee. In Nkonde and Grayson's oral history project she says that such work opened up possibilities of collaboration between civil society and the state.

“Before, the state did everything with managers, not with the people themselves [as organised groups],” she says. “In these projects, the intention was to decentralise control so that communities could make their own plans.”

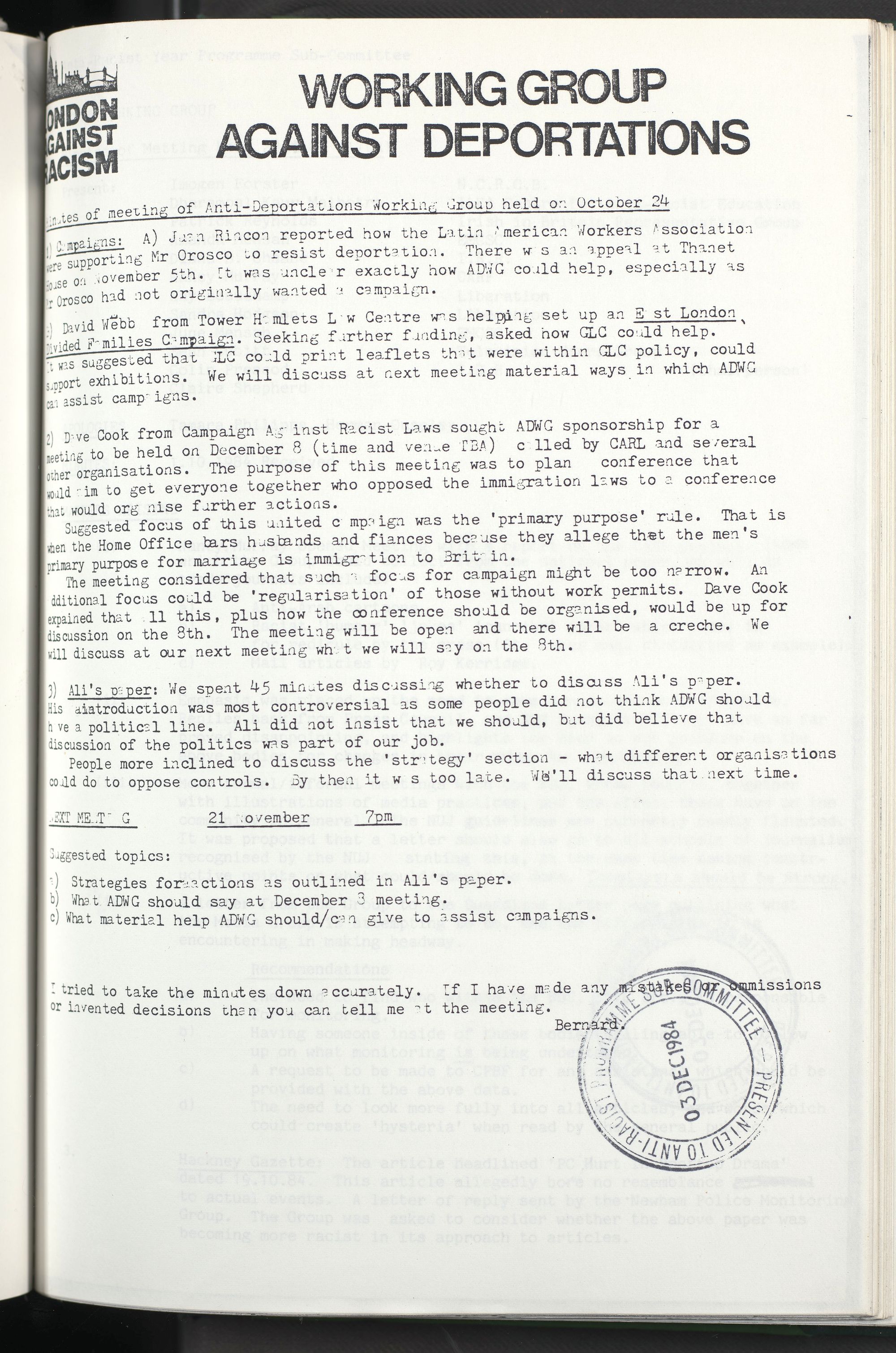

As part of the anti-racist year, the GLC set up working groups composed largely of non-official representatives from community campaign groups who met around subjects such as policing, education and immigration. The minutes reveal plans for projects that could not be realised and suggests why – whether it was due to disagreement, or difficulties with resourcing.

For anyone with an interest in social justice, local politics past and present is a fruitful place to investigate. As custodians of artefacts and archives, heritage workers in particular have a reason to engage with public policy to better serve their communities. The question for them to explore, with others, is how to use culture to make change.

When Conservative party leader Margaret Thatcher was re-elected in 1983, she announced plans to abolish the GLC. Many of its plans were thus cut short or reimagined. Documents at the London Metropolitan Archives show a lingering sense of doom.

The foreword of one report summarising the cultural activities of the past seven years uses a poetic analogy: “A dancer may perform with an aching ligament… and regard it as a point of honour never to let the audience know. We judged that the GLC’s cultural initiatives were of such importance that a record of the struggles and achievements, and a signpost for the future, should be produced, albeit with imperfections.”

For a government report, its words are surprisingly emotive, even melodramatic. Above all, they are a reminder that we must build current social movements with a concern for what has come before.